Foster + Partners Translates Architectural Classicism into Modernism at the Narbo Via Museum in France

Some commissions might tempt an architect to dial back time. But for the Narbo Via Museum in Narbonne, France, which displays Roman antiquities, Foster + Partners eschewed pediments, columns, capitals, or other elements of literal historicism. Rather the firm worked in a completely contemporary architectural language, combining state-of-the-art concrete construction, prefabricated building components, and simple notions of mass and spatial gravitas to evoke ancient building traditions.

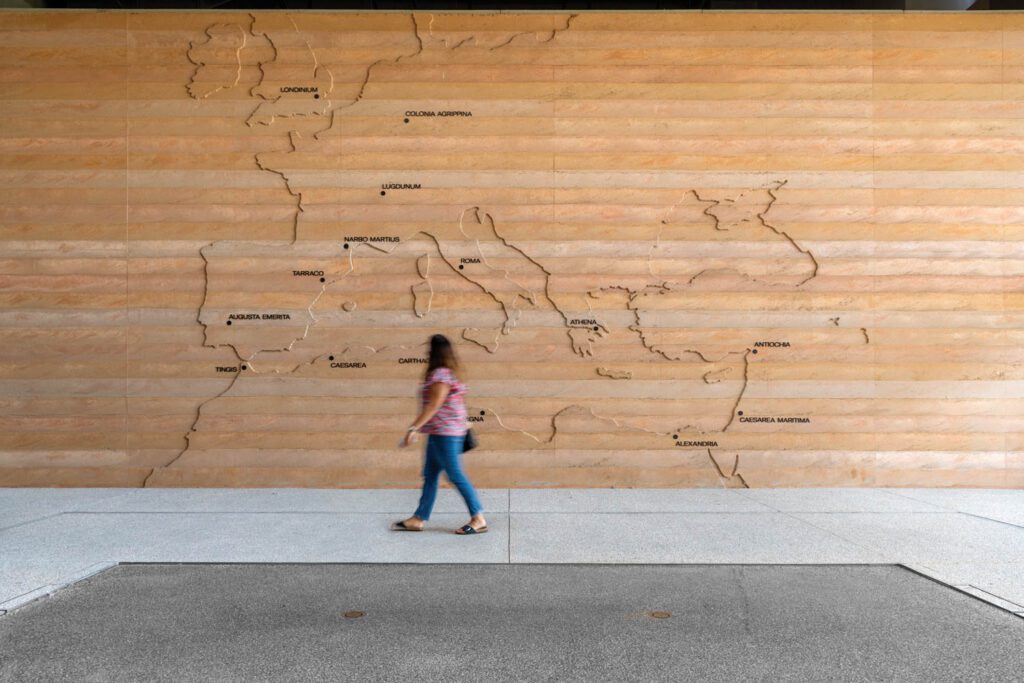

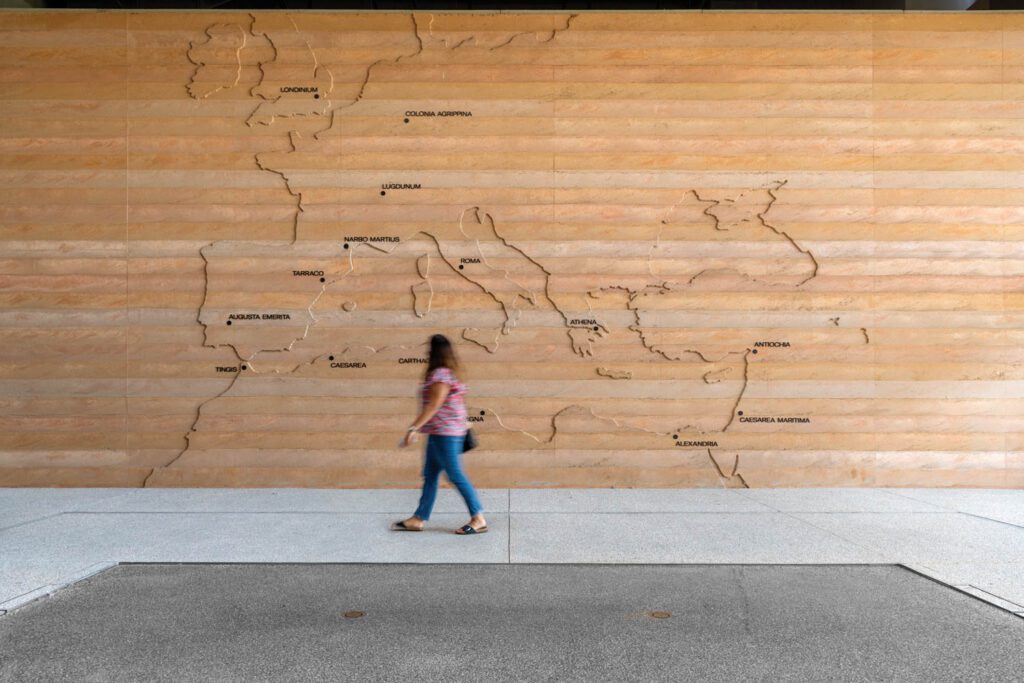

Present-day Narbonne was once Narbo, the first capital of Roman Gaul, and an important Mediterranean riverine port. In the Middle Ages, the city’s Roman buildings and funerary monuments became quarries for constructing fortified walls. Centuries later, in the 1860’s, when the walls were dismantled for a modern, expanding city, antiquarians retrieved stone blocks carved with figures and texts, and stored them in stacks in a Romanesque church. In 2012, Narbonne held an invited competition to build a regional museum and study center for the reliefs, one that would also serve, more broadly, as an introduction to all of Rome in the south of France. The blocks needed a controlled, protective environment, a more effective method of display, and facilities for conservation and research. The ruins of a Roman villa had also been discovered 20 years before, and they needed special accommodation, too.

With their mastery of concrete and masonry, Romans were inspired engineers and builders. But they were, in their way, proto-modernists, producing construction components in a handcrafted “industrial” process for what we would now call systems design. Just down the road in Nîmes, a 24,000-seat amphitheater offers an early example of a systems building, with stones—modular, fitted, and carved, some in distorted, non-Euclidean geometries—that were all sized and shaped for designated positions in the oval structure.

That Roman savoir faire established a precedent for the Foster team, which approached the project with comparable respect, skill, and efficiency, but in an industrialized systems design. Founder and executive chairman Norman Foster himself Romanized the agenda: “Norman was very insistent that if we were expressing the design as massive, it should be massive, to refer to the language of Roman architecture, instead of covering a frame with finishes, as we normally do,” partner and project architect Hugh Stewart notes.

Like a Roman military formation going into battle, the 104,300-square-foot building is square in plan, with walls of dry-packed, pigmented concrete manually tamped in layers—rosy striations that recall the sedimentary rock canyons of Petra, Jordan, carved with Hellenistic funerary temples. Organized in strict rectilinear geometries, the weighty, 32-inch-thick walls convey a monumentality whose traditions reach beyond Rome back to ancient Egypt’s Karnak.

A tall, cathedral-like hall divides the building into two rectangular sections. The soaring space houses more than 800 funerary stones, which are stacked in a clifflike grid of galvanized-steel racks. This is the public-facing side of an industrial storage system with a factory-style gantry that allows museum staff on the other side to retrieve any artifact needed for study or conservation. Otherwise, the stones remain in full view of museumgoers, who can access information about them on interactive touchscreens. Dubbed the lapidary wall, the enormous structure turns what would normally be a back-of-house area into an exhibition hall.

The prefabricated concrete roof extends beyond the load-bearing perimeter walls, providing shade from the meridional sun. Since the museum sits on a plinth, all HVAC ducts and the like run under the floor—another very Roman idea—leaving the underside of the roof as an unadorned ceiling. The interior spaces are modular, “to allow a large degree of flexibility and also an interpenetration of public and professional zones,” Stewart says. “The modular approach to planning gives you all sorts of visual axes penetrating the plan.”

The public entry is like the atrium of a Roman house, a lofty courtyard centered on a shallow reflecting pool with a roof opening above. It leads into the larger of the museum’s two constituent sections, which houses galleries for temporary and permanent exhibitions (including appropriately scaled spaces for frescoes and other artifacts from the ruined villa) along with a restaurant, shop, and small auditorium. Meeting rooms, administrative offices, workshops, and research areas occupy the smaller of the two sections, on the other side of the lapidary wall.

With its dry-packed walls, precast-concrete roof, galvanized-steel storage racks and fittings, and polished concrete flooring, the museum is “a true brutalist building: no finishes on anything,” Stewart acknowledges. “The project harks back to the early days of Foster Associates as a kind of modular, lightweight structural building but with a single big difference: much heavier construction.” For a museum about classical architecture, the firm has a produced a classic of modernism that in its clarity, purity, and spare monumentality achieves, without historical pastiche, the authenticity of a Roman building. The two traditions coincide in a regular, repetitive, engineered structure—the language of both.

project team

product sources throughout

read more

Projects

CannonDesign Transforms the Interiors of a Former Newspaper Building into Modern Tech Offices

Vintage printing machinery, housed in a former newspaper building, enlivens new offices for Square and Cash App in St. Louis.

Projects

Sculptural Installations Enliven LSM’s Washington Office for Paul Hastings

In LSM’s Washington office for eminent legal firm Paul Hastings, a pair of tall sculpture installations evoke and defy the laws of logic.

DesignWire

Luo Studio Transforms a Warehouse into a Medicinal-Plant Mecca in Jiaozuo, China

Using local pine, Luo Studio transformed a warehouse into a medicinal-plant Mecca, building green and revitalizing industry in Jiaozuo, China.