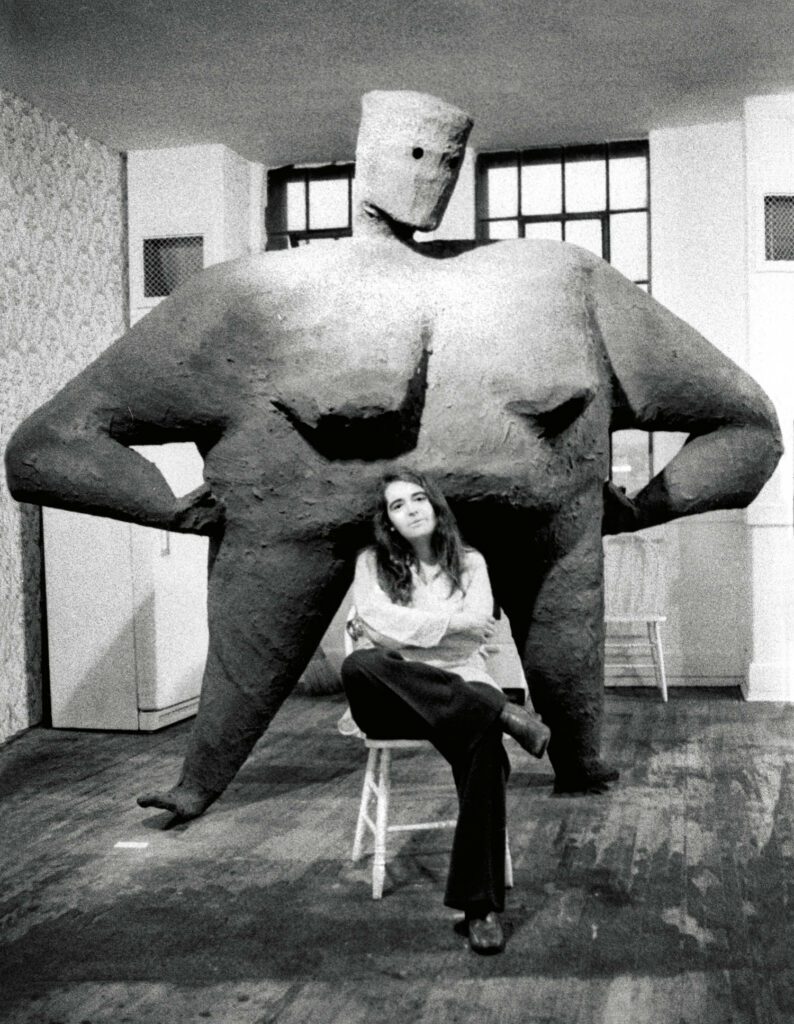

Salon 94 Design Restages Kate Millett’s Judson installation, ‘Fantasy Furniture, 1967’

In the mid 1960’s, Kate Millett was busy creating a series of anthropomorphic pieces of furniture in her New York one-bedroom apartment, which she shared with her then-husband, sculptor Fumio Yoshimura. Fresh from studying sculpture in Japan, the thirtysomething feminist theorist, activist, and artist found herself surrounded by the DIY creativity of downtown Manhattan. The local hardware stores, cabinetries, seamstresses, and cobblers on the Bowery, where Millett lived, provided her with the material resources for carved-wood stools with human legs and leather shoes, a piano with its own pair of hands hovering above the keyboard, and other household items with humanoid appendages.

In 1967, the Judson Gallery, one of the era’s most influential avant-garde art spaces, exhibited the witty pieces in an interior-like installation titled “Furniture Suite.” Millett’s seminal book Sexual Politics, which, like her artwork, critiqued patriarchal domesticity, would come out three years later, establishing its author as an international feminist leader whose fame would carry her to the cover of Time magazine in August of 1970.

For more than five decades, the nine objects sat in the Upstate barn Millett shared with her life partner, Sophie Keir. Seeing guests interact with the pieces over the years encouraged the artist to expand Fantasy Furniture, as she came to refer to the collection. But she never made a return to the series. “A woman doing more than one job was quite unusual at the time. As a compartmentalized thinker, Kate felt her scholarly work was being questioned due to her furniture-maker side,” notes Kier, who runs the late artist’s estate.

This winter, however, New York gallery Salon 94 Design restaged the Judson installation as “Fantasy Furniture, 1967.” “I was fascinated by how Millett diffused an element of play to her anger for being stuck with inanimate house objects and a husband,” Salon 94 owner Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn says. “As a scholar who was so occupied by women’s rights, she had to develop a sense of humor to stay sane,” Keir adds. The show demonstrated that the human-furniture hybrids still hold a punch, playfully tackling the dysfunction of domestic union and codependency.

Today, Keir and Greenberg Rohatyn rank Millett the artist alongside her New York contemporaries Marisol Escobar, Yoko Ono, Yayoi Kusama, and others who cemented the period’s boundary-pushing women’s art. “A time capsule of feminist history,” is how the dealer describes the show. As a new generation discovers Millett’s oeuvre on gender liberation, Keir believes her partner’s art furniture will be a significant part of the revival.

read more

DesignWire

Don’t Miss a Chance to Enter Interior Design’s Hall of Fame Red Carpet Contest

Interior Design and Swedish-based Bolon are teaming up to host a red carpet design competition for the Hall of Fame gala in New York.

DesignWire

Ukrainian Designers Speak Out on the Current State of Affairs

Following the Russian invasion, these Ukrainian designers tell Interior Design about the current reality of their work and home lives.

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Dustin Yellin

Artist Dustin Yellin chats with Interior Design about finding the right light and the performative aspect of his sculptures.