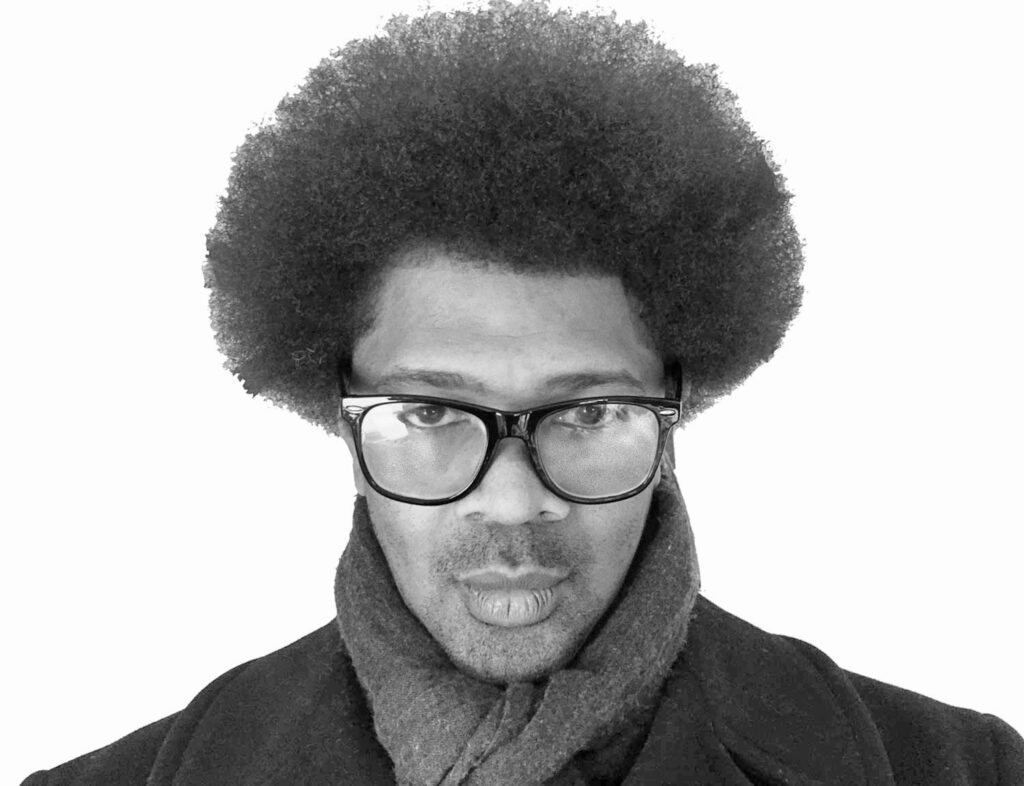

10 Questions With… Stephen Slaughter

Stephen Slaughter cannot wait to get settled in New York City. “I heard that the only thing consistent in New York is change, and that applies to architecture, too,” says the newly appointed chair of undergraduate architecture at the Pratt Institute School of Architecture. For Slaughter, known for weaving academic work with social engagement and urban advancement, in and out of the studio, a leadership post in the heart of Brooklyn is the perfect fit.

Change, unorthodoxy, and justice are core pillars of his practice and decades-long career as an educator. These ideals, however, are also critical in his role as an activist who collaborates with non-profit organizations for urban advancement, especially around Ohio where he is currently based as a visiting professor in the School of Architecture and Interior Design at the University of Cincinnati.

Looking ahead to his new role and life in Brooklyn, Slaughter shares insights on the symbiotic relationship between architecture and the communities it shapes with Interior Design.

Interior Design: Let’s start with accessibility. While architecture is inherently a form of accessibility, the pandemic has changed the way many approach the practice. Could you talk about your experience and observations regarding access in the last two years?

Stephen Slaughter: Speaking for myself, access has increased while operating remotely. I had opportunities to lecture and network in places that I normally would not. Engaging in conversations both on West and East Coasts via online platforms extended my outreach. I connected mentors and mentees to disseminate ideas and brought more people on board. Of course, Covid has had negative effects one people’s autonomy and the economy, but in my personal experience, it has expanded access just by virtue of remote education and by allowing communities to connect. Previously, these connections largely remained local and, for some reason, we didn’t see this type of communication as a necessity.

ID: You’re a first generation college student in your family. I am curious about the type of responsibility this generates on a personal level considering architecture as a practice involves another form of social responsibility.

SS: I am more conscious of my role in terms of the communities where I come from. This includes the church community I was raised in in Columbus, or the Black institutions I’ve been involved with, such as my fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha, which was also Martin Luther King Jr.’s fraternity. As a first generation college student, I am keenly aware of the benefit I gained from the eduction and the responsibility of reaching back to my communities, especially those that may not have the same privilege. There is a responsibility to understand where you come from to live your narrative. This might be more present in me.

ID: Architecture can also be a controversial field, especially considering its environmental impacts and relationship with the lands that buildings claim. You heavily collaborate with non-profit organizations, such as Watts House Project, Youth Hope Cincinnati and Elementz Hip Hop Cultural Art Center, which seem to emphasize the socially conscious aspect of architecture.

SS: This springboards from the responsibility I mentioned earlier. Putting on a collective effort has always been a part of what I am doing, not only in my practice but also as a citizen. Martin Luther King Jr. and his involvement with my fraternity has been an inspiration. I perceive my roles in architecture and in the society as intertwined.

ID: In this vein, collaboration is a crucial part of your work, especially in relation to urbanism, which is collaborative by nature. Living in cities as communities means we are constantly working together with one another.

SS: I engage with ideas that I find vital and through them, I build personal connections and find camaraderie with colleagues and friends. Collaboration facilitates itself through combining mutual talents and time with like-minded people, as well as a desire to make impact. I have been fortunate to meet people whose energies I am charged by. Conversations spin into action. In terms of a timeframe, it is hard to qualify because this has always been essential to my character. I don’t collaborate as a means to an end—it’s great to work with friends.

ID: You’ve cofounded PHAT to bridge architecture with art and exhibited in museums, such as Studio Museum in Harlem. This is an interconnected web between art and architecture as a practice and academic field. How do you see the presentation of architecture in institutional contexts and its contribution to your academic practice?

SS: An interdisciplinary track allows for expansive conversations with issues that may not be possible strictly in practice. Personally, I feel that an interdisciplinary role allows me to fluidly investigate different realities and conditions. Along the way, I enjoy the room for being critical. Academic criticality leads to artistic expressions that engage with issues that are key to me and to the community, such as identity and power.

ID: You started your career with working at Morphosis Architects under Thom Mayne in the late 1990s. Could you talk about the experience of being a part of a large team, especially as a person of color?

SS: I learned a lot from Thom and his practice, such as the power in architecture to make the world an inclusive place. At Morphosis Architects’s office, there was not a corner office because Thom didn’t believe in the hierarchy. His energy was reflected in the firm. His radical propositions about design is something that I carry with me. The splendor of design should not be reserved for a group.

ID: Looking ahead, have you had chance to observe the Clinton Hill neighborhood in Brooklyn where Pratt is located? There is burgeoning creative community in and around the school.

SS: I have been fortunate to travel to New York every year for the International Contemporary Furniture Fair to produce exhibits with students of collaborative classes between industrial design and architecture departments at the University of Cincinnati. Each year, I see the changes in the city. I am learning about Brooklyn as much as I can before setting up shop there. I cannot wait to call myself a New Yorker.

ID: There are 700 undergraduate students at the Pratt School of Architecture. What is your advice to them and to those considering a degree in architecture?

SS: I recommend them to detect things they learn at the institution and find their identities in the work they do and choices they make. Be a caretaker of those around them and be stewards of the earth and their communities. Be activists in and outside of their practices. Their roles as citizens is just important as practitioners of architecture.

ID: You have been described as someone who challenges conventional architectural orthodoxy, which is quite interesting. Could you elaborate on this notion?

SS: Challenging the orthodoxy is about understanding of things that have been consistent in pedagogical and disciplinary practices. It means thinking critical consistently and allowing the criticality to challenge molds and representations. It is about challenging ideas of convention, especially in the western canon. It is also about thinking other molds of construction and cultures that contributed to the architectural discourse but did not receive the credit. Unorthodoxy is about always questioning everything you’re a part of and along the way, finding what has been overlooked in conventional means and embrace and give voice to them.

ID: What are the differences between challenging the orthodoxy in academia as opposed to an architectural practice? Academia invests in the future while the result of studio practice is more immediate.

SS: While we mold the future and invest in the intellects of the next generation, academia is a speculative practice.

read more

DesignWire

Honoring Black History Month

In honor of Black History Month, the Interior Design team is spotlighting the narratives, works, and craft traditions of Black architects, designers, and creatives. See our full coverage here, including interviews with…

DesignWire

10 Questions With… David Brown

David Brown talks with Interior Design about church acoustics, the difference between the available and the vacant, and the possibilities of the temporary.

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Nina Cooke John

In an interview with Interior Design, Nina Cooke John speaks candidly about juggling responsibilities, realizing her first built public artwork, and the importance of active participation in civic life.

recent stories

DesignWire

Don’t Miss a Chance to Enter Interior Design’s Hall of Fame Red Carpet Contest

Interior Design and Swedish-based Bolon are teaming up to host a red carpet design competition for the Hall of Fame gala in New York.

DesignWire

Ukrainian Designers Speak Out on the Current State of Affairs

Following the Russian invasion, these Ukrainian designers tell Interior Design about the current reality of their work and home lives.

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Dustin Yellin

Artist Dustin Yellin chats with Interior Design about finding the right light and the performative aspect of his sculptures.